Although the majority of the land in the Upper Wapsipinicon River Watershed is farmed, there are public natural and recreational areas throughout the watershed. Natural areas in the corridor of the Wapsipinicon River have been targeted for public acquisition and management by city, county, and state partners. As a result, the Upper Wapsipinicon River Corridor has become one of Iowa’s premier wildlife areas.

The Wapsipinicon River Bird Conservation Area (BCA) was the 11th BCA to be dedicated in Iowa. Located in Bremer, Black Hawk, and Buchanan Counties, its core is made up of the Sweet Marsh wildlife Area and the Wapsipinicon River Greenbelt. The area has a great variety of habitats, including vital floodplain wetlands, forests, and grasslands. Containing approximately 88,000 acres, the Wapsipinicon River BCA contains valuable riparian habitat that is home to such species as the Sandhill Crane, Red-shouldered Hawk, American Woodcock, Black-billed Cuckoo, Red-headed Woodpecker, and Bald Eagle.

The bottomland timber lining the river corridor is important to a number of birds who rely on standing dead trees, like those in floodplain forest, to nest successfully. Marsh birds find suitable breeding habitat in the delicate wetlands along the river and numerous shorebirds and waterfowl use the area as a stopover point on their long migrations to their northern breeding ground. River corridors around the state of Iowa contain some of Iowa’s best preserved wildlife habitat but the Upper Wapsipinicon River BCA is an excellent example of a healthy riparian ecosystem that harbors many species of plants and animals. (Description from interpretive signage at Sweet Marsh in the Wapsipinicon River BCA. Additional information about specific species, management and history of Sweet Marsh, and the Iowa BCA program is available at Sweet Marsh.)

According to the Upper Wapsipinicon River Rapid Watershed Assessment conducted by the NRCS there are 58 plant and animal species listed as threatened, endangered, or species of special concern that inhabit the Upper Wapsipinicon River Watershed. The Iowa DNR has identified the threatened, endangered, special concern. and selected rare species that are defined as “unique”, for each county in Iowa. The database is called the Iowa Natural Areas Inventory (INAI) and is available to the public via the Natural Areas Inventory Interactive Mapping.

The table below shows the number of threatened, endangered, special concern and selected rare species defined as unique in each UWR Watershed county according to the Iowa Natural Areas Inventory. The UWR Watershed encompasses varying percentages of each of these counties and therefore an unknown subset of the total number of species by county is located within the UWR Watershed portion of any given county.

https://programs.iowadnr.gov/naturalareasinventory/pages/Query.aspx

An interactive map showing specific species occurrence within each county in the watershed is available at https://bison.usgs.gov/#home

| County | Number of Unique Listed Species |

|---|---|

| Howard | 69 |

| Buchanan | 59 |

| Black Hawk | 72 |

| Bremer | 58 |

| Chickasaw | 51 |

| Delaware | 82 |

| Fayette | 84 |

| Floyd | 41 |

| Jones | 67 |

| Linn | 96 |

| Mitchell | 52 |

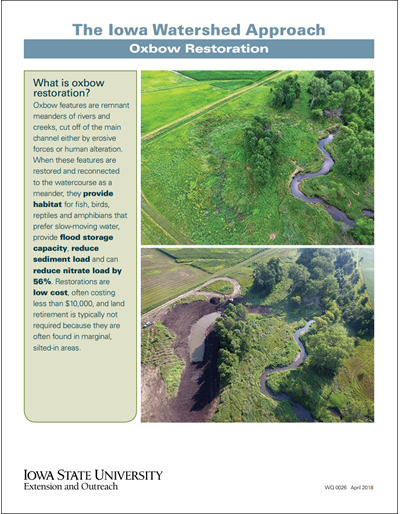

Oxbows

Oxbows are remnant, historic channels of rivers and streams. They are formed over time as part of the natural process of stream and river sedimentation and erosion when a river curve or “meander” naturally becomes so extreme that the physical flow of water is no longer optimal for river function. At that point, the course of the main channel is altered through a natural process that shortens the river flow by cutting across land and isolating the previous channel meander. Once the meander becomes physically isolated from the main channel it can become a dry depression, wetland, pond area, and in some cases an intermittent or temporary side channel. Human alterations to the channel or influences on river movement or natural processes can also create oxbows. Oxbows also provide flood storage, reduce sediment loading, and can reduce nitrate load by 55% (Iowa State Extension). Oxbow wetlands not only expand watershed resiliency, but they can also provide a variety of recreational activities such as fishing, hiking, bird watching, hunting.

“Five to seven million migratory waterfowl, including the endangered whooping crane, use wetlands, i.e. prairie potholes, as resting and feeding areas and as an abundant food source.” (Source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

Oxbow restorations can maximize and increase any or all of their benefits, including improving habitat for fish, bird, and reptile species that prefer slow-moving water. Some fish species, such as the Topeka shiner, a federal endangered species, totally rely on oxbow’s slow-moving water for reproduction habitat.

Fish Species

Breeding Birds

The Upper Wapsipinicon River Corridor and many of the natural areas in the UWR Watershed provide important habitat for many nesting and migratory birds, so much so that in 2007 the river corridor in Bremer, Black Hawk and Buchanan counties was designated as an Iowa Bird Conservation Area (BCA) for its diversity of bird species. This was the eleventh designation of a BCA in Iowa since the Iowa DNR Wildlife Bureau established the BCA Program in 2001. According to the Iowa DNR,

“The Bird Conservation Area (BCA) concept was first proposed by the Midwest Working Group of Partners In Flight (PIF) to maintain populations of breeding grassland birds. That has since been expanded to include birds breeding in a variety of habitats, including grassland, wetland, woodland, and savanna. This concept is backed by research that suggests viable bird populations require conservation efforts at a landscape-oriented level.”

As is typical in Iowa, the approximately 88,000 acres encompassed by the Wapsipinicon River BCA is centered on two important “core” public properties, Sweet Marsh Wildlife Area and the Wapsipinicon River Greenbelt. This BCA also includes a variety of other wetland-forest, wetland, and marsh areas that support migratory and non-migratory species, including Sandhill Crane, Red-shouldered Hawk, American Woodcock, and Bald Eagle.

The Iowa Breeding Bird Atlas II documents the specific species of hundreds of birds from over a dozen separate “blocks”, small land inventory areas, in the UWR Watershed. These bird inventories were completed between 2008 and 2012 and provide information about common, threatened, and endangered bird species in the UWR Watershed. According to the Iowa Breeding Bird Atlas, 129 different breeding bird species have been identified in the UWR Watershed, including thirty-five species listed on the Iowa DNR Wildlife Action Plan Species of Greatest Concern. Thirteen of those species are designated as rare, threatened or endangered in Iowa.

According to the Iowa DNR BioNet, which is the portal for sampling data and summaries of information collected from the Stream Biological Monitoring and Assessment Program, approximately 64 different species of fish have been identified in the Upper Wapsipinicon River Watershed. This includes the American Brook Lamprey and the Black Redhorse, which are listed as threatened species in Iowa. An upper, coldwater section of the Upper Wapsipinicon River also boasts brown and rainbow trout. Popular game fish in this river include walleye, northern pike, smallmouth and largemouth bass, crappie, bluegill, and channel catfish.

The Iowa DNR notes that,

“Many anglers consider the Wapsipinicon River one of the best all-around interior rivers in Iowa. The scenic 73-mile stretch of river, expanding through Bremer, Black Hawk and Buchanan Counties, offers great angling opportunities for a variety of game fish. Natural reproducing populations of smallmouth bass, northern pike and channel catfish thrive in this river along with a healthy walleye population maintained through walleye stockings. Navigation from Tripoli downstream to the small community of Littleton is mostly by canoe or kayak. Ten public access points along this section of river provide anglers access to an excellent northern pike fishery with fair populations of smallmouth bass, walleye and channel catfish. Navigation from Littleton downstream to Independence is mainly by canoe, kayak or small jon boat. The hard surface Otterville bridge access provides a takeout point for river users navigating downstream from Littleton or a launching point for those wanting to paddle through the impoundment above Independence. Smallmouth bass, walleye and channel catfish become much more prevalent throughout this section of the Wapsipinicon River. The river starts to widen and deepen downstream of Independence and jon boats become more common. There are six hard surface boat ramps and six public walk-in areas from the dam in Independence downstream to Troy Mills. This stretch of river offers fabulous angling opportunities for northern pike, walleye, smallmouth bass and channel catfish. In a 2014 Iowa DNR fisheries survey, staff measured and weighed over 280 smallmouth bass from the Three Elms Access located just downstream of Independence to the Old Iron Bridge boat ramp located several miles upstream of the small town of Quasqueton.”

Photo courtesy of Larry Reis

Threatened and Endangered Species

The US Fish and Wildlife Service report that the UWR Watershed may provide important habitat for several species of including the Indiana Bat (Myotis sodalis), Northern Long-eared Bat (Myotis Septentrionalis), Eastern Massasauga rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus), Smooth Green Snake (Opheodrys vernalis), Higgins Eye pearlymussel (Lampsilis higginsii), Sheepnose Mussel (Plethobasus cyphyus), Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus), Topeka Shiner (Notropis topeka), Dakota Skipper (Hesperia dacotae), Iowa Pleistocene Snail (Discus macclintocki), Poweshiek Skipperling (Oarisma poweshiek), Central Newt (Notophthalmus viridescens), Spetaclecase mussel (Cumberlandia monodonta), Pallid Sturgeon (Scaphirhynchus albus) and the Least Tern (Sterna antillarum). They also report the potential presence of several threatened or endangered flowering plants including the Western and Eastern Prairie Fringed Orchid (Platanthera praeclara and Platanthera leucophaea), Northern Wild Monkshood (Aconitum noveboracense), Prairie Bush-clover (lespedeza leptostachya), and the Western Prairie Fringed Orchid (Platanthera praeclara). The US Fish and Wildlife Service recognizes that

“more than half of all species currently listed as endangered or threatened spend at least part of their life cycle on privately owned lands, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) recognizes that success in conserving species will ultimately depend on working cooperatively with landowners, communities, and tribes to foster voluntary stewardship efforts on private lands. States play a key role in catalyzing these efforts. A variety of tools are available under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) to help states and landowners plan and implement projects to conserve species.”

More information about grants and funding opportunities related to endangered species protection and restoration can be found here. https://www.fws.gov/endangered/grants/index.html

Western Prairie Fringed Orchid photo courtesy of Larry Reis