Read this article (complete with photos) in the Des Moines Register

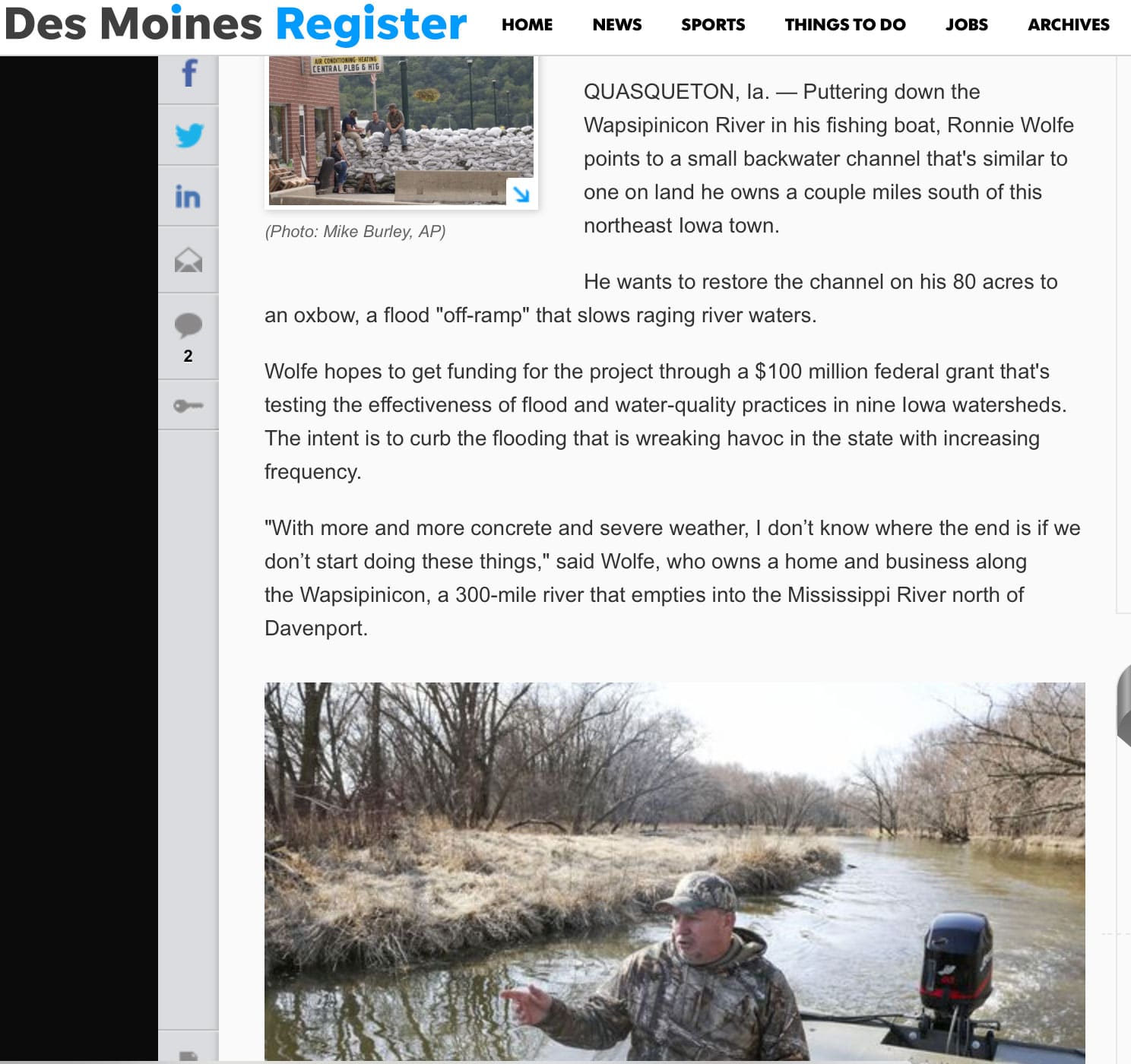

QUASQUETON, Ia. — Puttering down the Wapsipinicon River in his fishing boat, Ronnie Wolfe points to a small backwater channel that’s similar to one on land he owns a couple miles south of this northeast Iowa town.

He wants to restore the channel on his 80 acres to an oxbow, a flood “off-ramp” that slows raging river waters.

Wolfe hopes to get funding for the project through a $100 million federal grant that’s testing the effectiveness of flood and water-quality practices in nine Iowa watersheds. The intent is to curb the flooding that is wreaking havoc in the state with increasing frequency.

“With more and more concrete and severe weather, I don’t know where the end is if we don’t start doing these things,” said Wolfe, who owns a home and business along the Wapsipinicon, a 300-mile river that empties into the Mississippi River north of Davenport.

The state ranks fourth nationally in the number of floods since 1988, according to the study.

“We have a problem,” said Witold Krajewski, director of the Iowa Flood Center, at the University of Iowa.

The state has incurred 951 federal flood-related disaster declarations over nearly three decades, slamming every county in Iowa.

Some counties have been walloped as many as 17 times, according to the study.

“These are not floods of a lifetime,” happening once every 100 or 500 years, said Larry Weber, executive associate dean at the UI College of Engineering.

“We’re repeatedly impacted by floods,” disasters that are an economic drain on the state, said Weber, who co-founded the Iowa Flood Center with Krajewski.

Instead of just reacting to disasters, Iowa needs to look at long-term investments to reduce flooding and its damage, said Weber and Krajewski, who conducted the study with Antonio Arenas Amado, a UI assistant research engineer.

And an added benefit from the spending, researchers said, would be cutting Iowa’s water pollution, reducing the phosphorus that leads to toxic algal blooms and nitrates that can make water dangerous to drink.

Weber estimates that tackling the state’s flooding and water-quality problems would cost an estimated $10 billion over five decades to fix.

Without slowing and holding water in upstream farming areas, “the losses are simply going to go higher and higher and higher,” said Weber, who helped land the $100 million federal grant.

“Working with agriculture, we could transform the landscape in Iowa,” he said.

The scientists are sharing the impact with lawmakers, but Sen. Rob Hogg, D-Cedar Rapids, said the message isn’t fully landing.

“We made some progress,” he said. “There’s much more that needs to be done.”

‘Catch the water where it falls’

So far, Iowa’s flood work has been very focused on local responses, helping residents and businesses repair damage and move homes and buildings out of flood plains where possible.

For example, state, local and federal taxpayers have spent $175 million removing about 4,500 homes from Iowa flood plains since 1990.

That’s been effective, said John Benson, legislative liaison for Iowa Homeland & Emergency Management.

For example, removing 2,000 homes in eastern Iowa saved taxpayers $68 million in 2016 flooding, recouping about 90 percent of the $79 million spent removing the homes.

Historically, it takes three or four flood disasters to regain investments made through flood prevention efforts, Benson said.

But working upstream gives the state another way to approach its flooding problem, he said.

About $31.5 million from the federal grant is going toward flood-reduction projects in Dubuque and to help residents repair homes repeatedly hit with rising waters.

Another $40 million is being used in eight other watersheds to build wetlands, terraces, ponds and buffer strips, among other infrastructure.

“We want to do anything we can do to catch the water where it falls and retain it, so it’s not entering the river — or entering the river at a slower rate,” Benson said.

“We can use the land to help manage a flood. … That’s the future,” he said.

That’s important as Iowa faces another flood season.

Iowa faces a 50/50 chance of another round of flooding this spring, with rivers in northern Iowa already filled, Benson said.

A determining factor will be “how fast that snow-pack in northern Iowa and southern Minnesota” melts, Benson said. “That can change quickly.”

Iowa governor Terry Branstad visited Lyon and Sioux county to assess damage and visit with victims of flooding in Northwest Iowa on Wednesday, June 18, 2014.

‘The next big disaster’

Amado, the UI research engineer, said flooding is both “an urban and rural problem.”

Since 1988, flood damage to Iowa homes, factories and other property reached $13.5 billion, while corn, soybeans and other crop losses reached $4.1 billion.

Weber said upstream flood mitigation efforts help offset Iowa’s “100-year practice of draining the land.”

For decades, farmers have used underground drainage tiles to more rapidly move water into Iowa’s streams and rivers, making the state’s rich soil suitable for growing crops.

Cities like Des Moines “are increasingly realizing that there are limitations to what they can achieve when it comes to flood protection,” said Amado, of the university’s IIHR–Hydroscience & Engineering institute.

The Iowa Flood Center is working with Des Moines officials to assess what kind of protection the city could receive from flood-mitigation practices installed upstream.

“Imagine that you can build flood walls high enough — what about the communities downstream,” Amado said. “They will be impacted.”

One option to finance the $10 billion needed to tackle comprehensive flood mitigation is a proposal to increase the state sales tax three-eighths of 1 cent, Weber said.

A diverse group, including environmentalists, farmers and hunters, back adding the tax to generate about $188 million annually to boost water quality, outdoor recreation and wildlife habitat restoration, among other initiatives.

Sixty-three percent of Iowans voted for a constitutional amendment in 2010 to create a separate trust fund to clean the water and improve farm soil and wildlife habitat.

Republican lawmakers, who control the House and Senate, have resisted increasing the sales tax. Instead, in January, Gov. Kim Reynolds signed into law a $282 million water-quality package that environmentalists have criticized as inadequate to solve Iowa’s water problems.

Hogg said Iowa lawmakers are so focused on tax cuts this year that they’ve struggled to cover “even basic government services,” let alone look at long-term investments.

“It’s upstream management and retention and work we need to do to safeguard property downriver,” he said. “You’ve got to prepare for that next, big disaster.”

‘The river is my livelihood’

Wolfe knows his one oxbow isn’t enough to stop the Wapsipinicon River from flooding.

But he believes joining with neighbors throughout his watershed and others in the region could make a difference in the amount of devastation that downstream towns and residents see.

Buchanan County is one of nine Iowa counties that are among the top 15 percent nationally with the highest number of flood disasters per square mile.

“When it floods, I can’t drive to my house … that happens three or four days a year,” said Wolfe, whose home sits on a ridge above the river.

He has a similar setup at his restaurant and bar, Wolfey’s Wapsi Outback, which sits high enough off the river that it hasn’t flooded.

“I’m in a flood zone now. I never used to be,” said Wolfe, whose personal and professional life revolves around the Wapsipinicon River.

In addition to his concerns about flooding, Wolfe is worried about the health of the Wapsipinicon, in particular the damage soil carried into the river can cause, including increased silting and high levels of nutrients.

Hundreds of his customers come to the region each year to bike, kayak, fish and hunt on or along the river.

“The river is my livelihood,” said Wolfe, who pointed out a bald eagle on a recent spring day.

“I live on the river. I work on the river,” he said. “My whole life I’ve spent on that river. It’s a huge part of my life.”